The Cinema and Propaganda in the Second World War

The Cinema and Propaganda in the Second World War

More than one billion cinema tickets were sold in the UK in 1939, and attendance climbed throughout the conflict, peaking at 1.06 billion in 1946. Cinemas closed briefly after war broke out, then rapidly reopened. US admissions were over three times higher, reflecting population size. In Germany, films were equally popular. With audiences this large, studios, film-makers, and governments leveraged movies for propaganda. Radio and print also played major roles.

Two of the worst films I have seen are unabashed flag-wavers: Big Jim McLain (1952) and The Green Berets (1968). Neither is set in the Second World War—one belongs to the McCarthy era, the other to Vietnam—and both starred John Wayne. That an Oscar-winning actor (True Grit, 1969), superb in Stagecoach (1939), The Quiet Man (1952), and The Searchers (1956), could appear in such material is hard to comprehend. Most propaganda films are turkeys. Some are exceptional. I admit I missed the true quality of a few when I first saw them years ago.

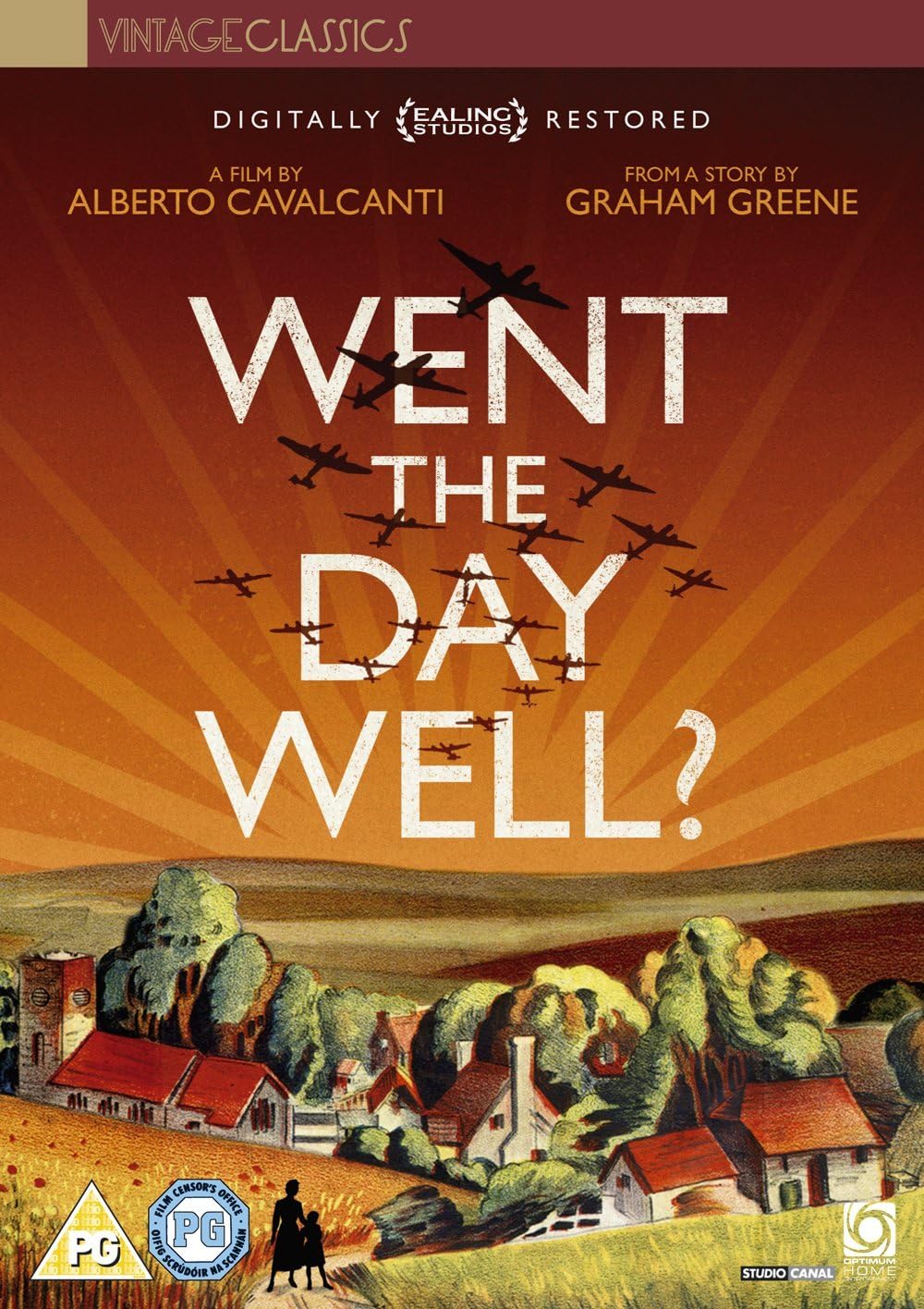

Went the Day Well? (1942)

Directed in Britain by the Brazilian-born Alberto Cavalcanti from a story by Graham Greene, Went the Day Well? imagines a quiet English village infiltrated by German soldiers posing as British troops on exercise. At first the invaders seem decent; once revealed, they are vicious and remorseless. Worse is the unmasking of an English collaborator, previously a respected villager. The locals respond with courage and resourcefulness. Audiences left convinced of Nazi evil, alert to fifth columnists, and confident that British character would help win the war.

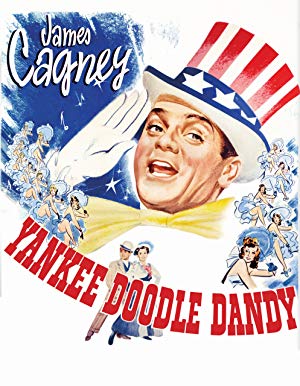

Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)

Entirely different yet no less effective is Yankee Doodle Dandy. I long assumed it typified Hollywood’s Golden Age: great songs, dazzling choreography, and an Oscar-winning turn by James Cagney. There is more. The film traces the life of George M. Cohan—born on the Fourth of July—whose patriotic energy dominated early 20th-century American musical theatre. In a pivotal scene, Cagney plays the piano as troops in Northern France, 1917 sing Cohan’s “Over There.” The number returns at the end as American soldiers march to win the war against Germany and Japan. Shooting began just after Pearl Harbor (7 December 1941), and the studio rushed completion by May 1942 to lift morale as the US entered a war many had wished to avoid.

Joseph Goebbels and Ufa

Germany naturally pressed cinema into service. Ufa had crafted inter-war masterpieces such as Metropolis (1927) and The Blue Angel (1930), yet figures like Fritz Lang and Marlene Dietrich left as the Nazi threat grew. Under Joseph Goebbels, the regime tightened control and quality declined. As war neared, German screens filled with cheap quickies in which Aryan heroes confronted Jewish villains.

During the war Goebbels pushed films aimed squarely at enemy nations. A clear example is Titanic (1943). The plot blames the White Star Line’s owners for pressuring the captain to chase a speed record, while a German First Officer is the voice of caution and the hero during the sinking. The ship’s Jewish engineer is scapegoated. The film saw limited release in occupied Europe but was not shown inside the Reich, as propagandists feared its tragic tone would depress civilians while the war was going badly. Some footage later appeared in the British film A Night to Remember (1958).

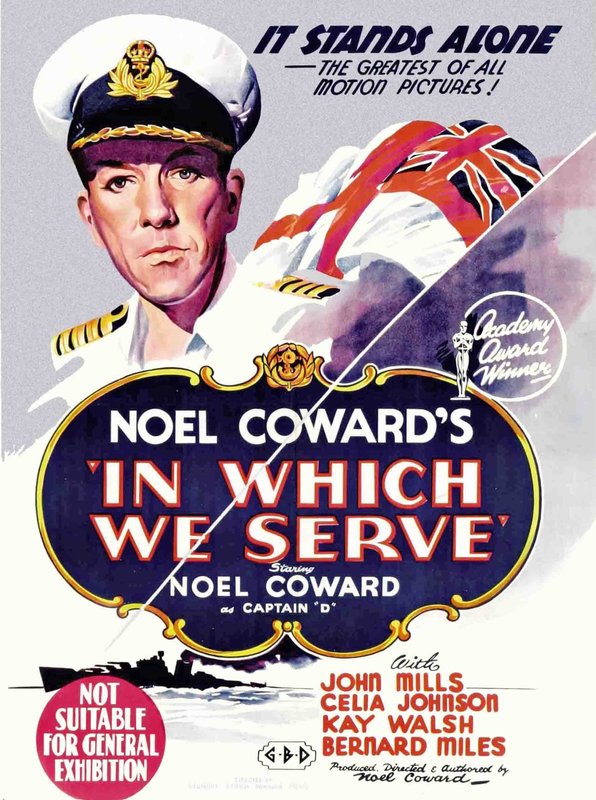

British state influence and flagship titles

Government involvement in UK production was visible. One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942) was sponsored by the Ministry of Information. The most famous wartime propaganda film was In Which We Serve (1942), backed fully by the Ministry and inspired by a recent naval action involving Lord Louis Mountbatten. Its strength lay in showing the war’s impact across classes and reminding audiences that sacrifices—including the ultimate sacrifice—were required for victory.

The narrative follows the sinking of a British ship during the Battle of Crete. Mountbatten recounted events to Noël Coward, who starred, wrote the script and music, produced, and co-directed with the future great David Lean. Audiences spilling out of bomb-scarred cities grasped the scale of the challenges ahead yet felt confident their country could prevail.

Conclusion

All sides churned out quickly made flag-wavers during the war. A few rose above the form. Went the Day Well?, Yankee Doodle Dandy, and In Which We Serve work as propaganda and as great movies in their own right.