Crime in the London Blitz

- David Lowther

- July 6, 2025

- 5 mins

- History World War Two

- blitz crime fiction london

CRIME IN THE LONDON BLITZ

1939 - 1945

Wartime London in My Novels

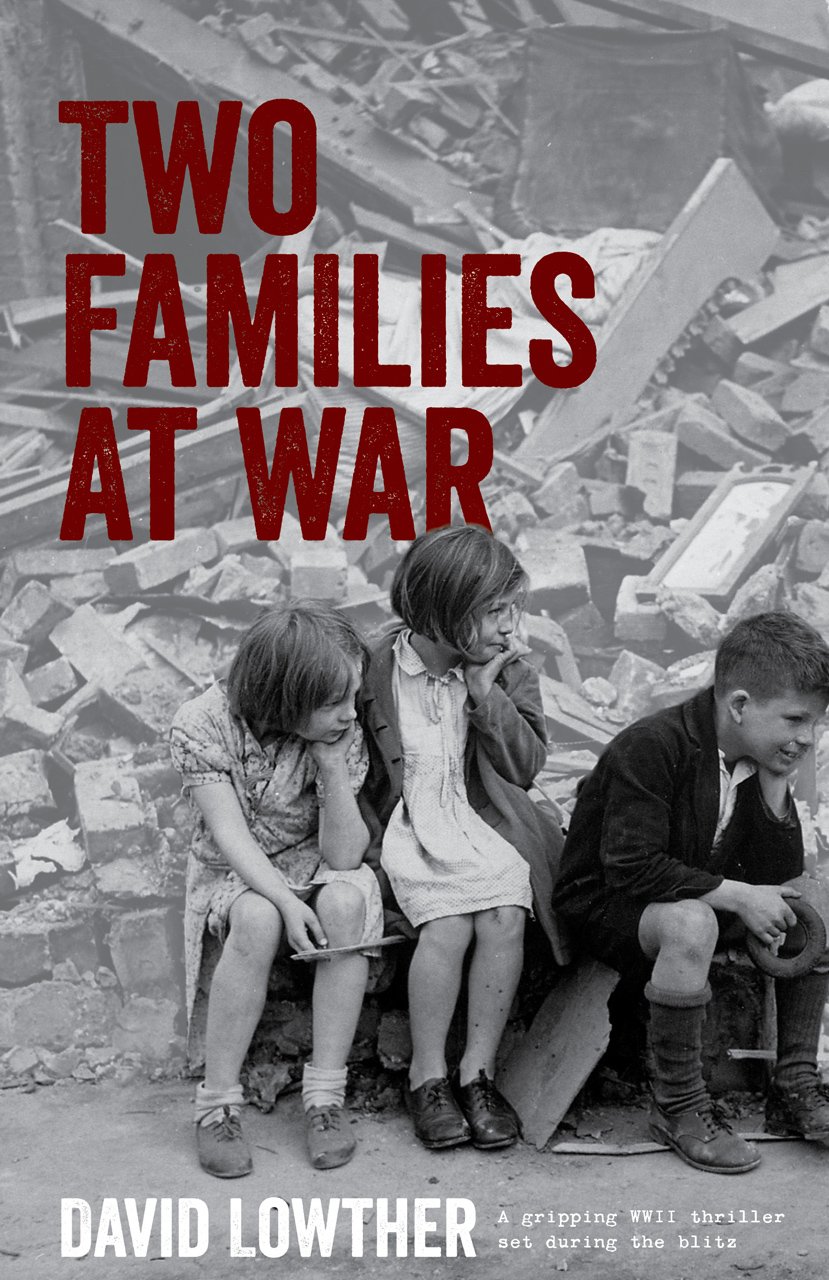

Two of my four novels written about events before and during the Second World War were set partly during the London Blitz. The first of these, Two Families at War, told of a small family of Jewish refugees from Germany who clash violently with a crime family in North London. The most recent, Ordinary Heroes, begins with two older teenage boys who become civil defence volunteers at the start of the Blitz in September 1940.

Crime and Opportunity in the Blitz

All categories of crime increased during the war. The blackout, and later the Blitz, were the criminals’ friends, allowing thieves and even murderers to go about their business amidst the confusion and darkness, right from the outbreak of war in September 1939. Various Acts of Parliament, passed as part of Emergency Powers, created a new kind of criminal — the forger who printed fake ration cards, food and other coupons and ID cards. Some criminals skipped the forgery option and raided warehouses and offices where the unused documents were stored.

Vice and Treachery in Wartime Cities

Prostitution flourished in all of the UK’s cities. In London, ‘ladies of the night’ plied their trade at a number of venues, mostly in and around Piccadilly Circus, where the Regent Palace Hotel provided servicemen on leave with warm comfort as it had during the First World War.

And then there were traitors who actively aided the enemy. John Amery, whose father Leo had held senior government positions since the late 1920s, was executed for high treason in 1945. Shortly after this, William Joyce — better known as Lord Haw-Haw — suffered a similar fate for the same offence. In all, fifteen UK citizens ended their lives at the end of a rope for betraying their country during the war.

Looting: The Worst of Blitz-Era Crimes

Perhaps the worst of these criminals, whether organised crime groups or individuals, were the looters. When the first bombs fell in September 1940, thieves immediately seized their chance. Full air raid shelters meant empty houses and opportunities for the criminals. Many folks returned to their properties to find them ransacked. As the nights drew in, the robbers began to visit the empty houses of wealthy Londoners who had fled to the safety of their country properties to avoid the bombs.

Looters often raided houses while raids were taking place, sometimes dressed in civil defence uniforms which they were not entitled to wear. Criminals stooped to their lowest levels at the bombing of the Café de Paris in London’s Coventry Street in March 1941.

The Café de Paris Tragedy

The Café de Paris was a popular London nightclub and the fun was in full swing when, just before ten in the evening of March 8th 1941, a 50kg high explosive bomb struck the premises, killing more than thirty people and injuring many more. This was one of many mass tragedies in the Blitz, but what made it infinitely worse was that, as soon as the bombers flew away, the looters arrived and began to steal from the dead and the dying. Witnesses too stunned to react later reported seeing thieves hacking off fingers of corpses to get hold of their rings.

I used the Café de Paris bombing in my novel Two Families at War, though I turned to poetic licence to shift the location to the north end of Soho to fit the narrative (rather like the film director Steve McQueen who also adopted poetic licence when transferring the Balham Tube disaster to a different location in his superb film Blitz).

Real Events in Fiction

The desecration of corpses to secure rings and other jewellery also figures in one of the action sequences in the early part of my most recent novel Ordinary Heroes.

Ken ‘snakehips’ Johnson, died March 8th 1941 in the Café de Paris bombing

Reflection and Reading Recommendations

This has been a small introduction to crime in the Blitz. A majority of my novel Two Families at War is set against this background, while the early part of Ordinary Heroes covers similar ground — but not the nightclub bombing.

It is worth remembering that the vast majority of the citizens of Britain’s Blitz-hit cities were courageous, crime-free, helped those less fortunate than themselves and readily volunteered to carry out very demanding and dangerous tasks. The ‘Blitz Spirit’ was real.

Mark Ellis’s books featuring DCI Merlin are excellent Blitz-set reads, as are John Lawton’s fine novels — with Black Out the stand-out.

One outstanding non-fiction title that I can recommend to interested readers is Wartime Britain 1939–1945 by Juliet Gardiner.

A gold mine of information about the Blitz is, of course, the newspapers. Some can be found online, but all can be viewed at the Newspaper Library at St Pancras in London, part of the British Library.

Where to Read More

And don’t forget my novel Two Families at War — real events involving fictional characters.

Available from Sacristy Press and Amazon.