Collaboration in the Second World War

- David Lowther

- February 7, 2026

- 4 mins

- History World War Two

- collaboration france occupation quisling resistance vichy

COLLABORATION IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR

In recent years a wave of films and books has turned the spotlight on collaboration—the citizens of occupied countries who chose, or felt compelled, to work with their conquerors. I had long known collaboration existed, but the scale and complexity only hit home when I began researching for this post. What follows is a reader’s tour through the history, the moral knots, and the aftermath.

A spark in Bordeaux

My curiosity was kindled by Alan Massey’s detective novel Death in Bordeaux and its sequel Dark Summer in Bordeaux. Hearing Massey speak about his fascination with occupied France and Vichy pushed me to dig deeper. Soon after, two films—The Round-Up and Sarah’s Key—drove home a grim truth: in France, the mass arrest and deportation of Jews was largely executed by the French police, directed by the Gestapo and SS.

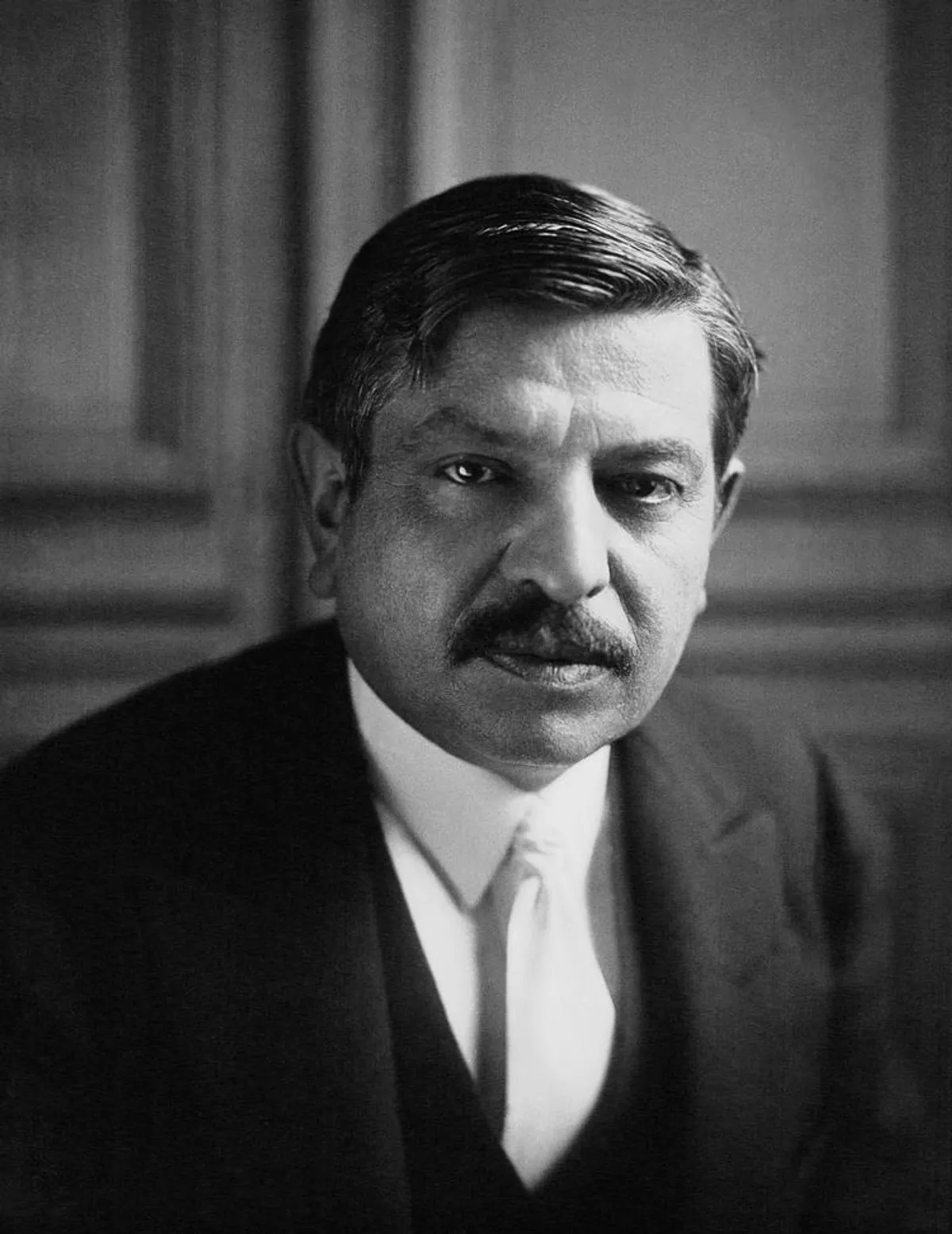

The policy had vocal champions inside Vichy. Marshal Philippe Petain and Prime Minister Pierre Laval both embraced anti-Semitism and anti-Communism. Tried after the war, Laval was shot by firing squad; Petain’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

Collaboration for ideology and survival

France was not unique. The 2011 Polish film In Darkness shows Jews hiding in the sewers of Lwow (now Lviv). Their most implacable pursuers are not German soldiers but the Ukrainian militia, hoping cooperation would earn independence from the Soviet Union. Elsewhere, some collaborators acted out of political conviction, others from fear or opportunism, and many ordinary people simply kept their heads down, waiting for the war to end.

Everyday choices, filmed without varnish

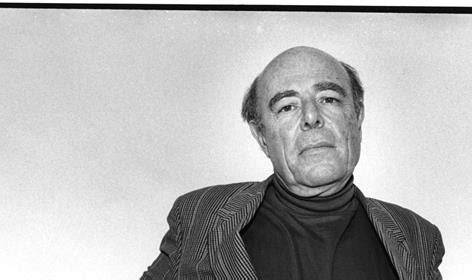

Marcel Ophuls’s landmark documentary The Sorrow and the Pity strips away post-war myths. Set in Clermont-Ferrand, it interweaves testimony from resistants, townspeople, German soldiers, SOE agents, and the bourgeoisie. The film’s most harrowing images show public head-shavings of so-called horizontal collaborators—women who had relationships with German soldiers. Ophuls was denied an Oscar for this film but later won for Hotel Terminus.

Reckoning after liberation

When occupying forces withdrew, vengeance often arrived first. Lynchings and summary shootings spread through parts of France, Italy, Greece, and Eastern Europe until Allied authorities re-established courts. Some cases became synonymous with betrayal. In Norway, Vidkun Quisling—whose very name became shorthand for treachery—was executed by firing squad after years as a Nazi puppet.

Historians like Keith Lowe, in Savage Europe, chart how long the score-settling lingered: in some regions partisans continued to mete out punishment well after 1945.

Would Britain have collaborated

Britons often assume they would have stood firm under occupation, but Channel 4’s documentary Churchill and the Fascist Plot suggests the picture might have been muddier. It profiles Archibald Maule Ramsay, a pro-fascist MP and founder of the Right Club—whose members included William Joyce (“Lord Haw-Haw”). Ramsay was interned without trial in 1940 yet returned to Parliament in 1944. My novel The Blue Pencil gives him a brief, sinister cameo.

Reflecting on a Dutch friend’s praise for the resistance epic Soldier of Orange, I admitted that Britons were never truly tested. Without occupation, we cannot know how many would have resisted, collaborated, or simply endured.

Why this matters

Collaboration was not a single story of villains versus heroes. It was a spectrum shaped by fear, ideology, survival, and sometimes love. Understanding it helps us read wartime choices with humility—and reminds us that occupying powers rarely rule without local help. I hope this overview encourages you to explore the subject further; the shadows of those choices still fall across Europe today.